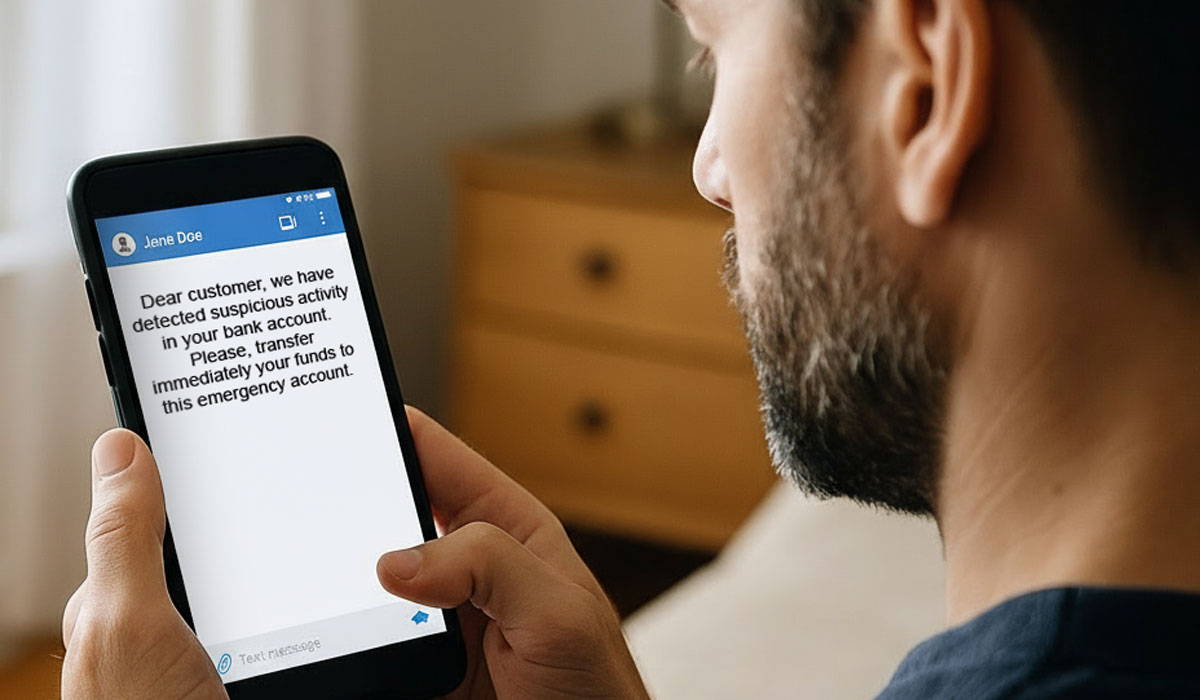

"This is your bank's security team. Your account is at risk."

What are Bank Impersonation Scams? A bank impersonation scam is where fraudsters pose as a legitimate bank to con the bank’s customers into taking...

Singapore’s new Protection from Scams Act comes after scam victims in the Southeast Asian island state lost $1.1 billion in 2024 alone. Read on to find out what this new regulation is all about and why it’s unlikely to solve the country’s scam epidemic on its own.

Under the new law, Singaporean Police can issue Restriction Orders (ROs) instructing banks to temporarily block transactions, ATM use, and credit services where there’s a “reasonable belief a person is about to send funds to scammers”. ROs can run up to 30 days and be extended up to five times to a maximum of 180 days.

People subject to an RO can still access funds for legitimate needs (e.g., daily expenses/bills), but any use of funds will be at the police’s discretion. The Protection from Scams Act came into effect in Singapore on July 1st, 2025.

The PSA complements pre-existing efforts to reduce the impact of fraud in the country:

Scams have soared to record figures partly because payments are often authorized by the customer during a convincing impersonation flow. Money locks only tie down certain proportions of account funds, while kill switches only help when customers recognize danger and act. ROs address the stubborn cases where people may authorize payments even after being warned they’re about to be conned.

This is a radical change. Critics might see the PSA as intrusive. A state-triggered pause on someone’s own money, based on “reasonable belief,” risks false positives, delays legitimate payments, and normalizes external control in day-to-day banking. Not to mention how having an active bank account is essential for receiving a salary or even to pay for water or electricity - which are basic needs for most.

If invoked too broadly, it could erode confidence and nudge people toward less regulated rails. That’s the overreach case, and it’s clear. But the authorities have naturally tried to ease such fears by saying they’ll only use a restriction order as a last resort measure.

The other side of the argument is that some victims can’t self-protect in the moment. Lures set by fraudsters routinely override sound judgment. The new law means that those close to potential victims, like family and friends, can inform the police about likely impending scams, who can then step in and prevent potentially big losses.

Some customers may find the intervention (i.e., inability to send money or use ATMs) intrusive, especially if the bank or police judgment is disputed. At the end of the day, determining “reasonable belief” that someone will transfer to a scammer is a judgment call that can go wrong.

On the flipside, customers benefit from a final deterrent in place for those cases where particularly vulnerable segments of society are scammed. Or the scam just seems so convincing that warnings from friends/family go unheeded.

By giving police pre-emptive freeze powers, Singapore introduces systemic friction into modern scam flows. Scam operations will need to distribute risk across more mules and micro-transactions to reduce suspicion.

Still, though, most scams are likely to continue as before. The law can’t predict intent out of thin air; it intervenes only when someone knows a person is at imminent risk. That means early use will likely catch edge cases where potential victims’ families or friends have raised red flags. Or it’ll catch cases already under investigation where police have traced mule accounts.

On the banking side, this new power represents a strong move toward an interventionist policy. It’s perhaps unsurprising when you see the fraud figures in Singapore continuing to trend in the wrong direction.

But the PSA doesn’t replace the need for fraud detection. In fact, being issued an RO exposes situations in which the bank’s detection measures arguably weren’t good enough. The real hazard for banks here is believing the RO is a safety net big enough to relax upstream monitoring. In other words, if this is viewed as a reason to get complacent rather than strengthening fraud detection.

In an APP scenario, the customer authorizes the payment (albeit under false pretenses), so fraud prevention must intervene earlier. What should be happening is greater investment in proactive, earlier fraud-detection and prevention.

If a Restriction Order represents a last line of defense, banks still need a first line that identifies the risk before suspicion from friends/family or external intervention become factors.

Instead of waiting for law enforcement to flag accounts, Acoru gives banks the tools to act on pre-fraud signal intelligence by detecting anomalies in account behavior before they crystallize into losses. By placing the account itself at the center of fraud strategy, rather than the transaction, Acoru enables banks to understand relationships and behaviors across their entire ecosystem.

Through continuous account classification, every account, whether it belongs to a potential victim or money mule, is scored and re-evaluated in real time as new signals emerge.

Omnichannel data orchestration unifies signals from payment networks, digital banking, messaging, and card activity into one continuous fabric of intelligence. It’s not enough to monitor multiple channels independently. Acoru connects them to reveal hidden links that would otherwise go unnoticed until it’s too late.

Acoru helps banks become more proactive and empowers them to spotlight money mules, the common denominator in both authorized and unauthorized fraud. By surfacing pre-fraud signals across all customer interactions and counterparties, banks can block complicit or high-risk accounts.

Singapore’s new law follows in the wake of figures that reveal fraudsters are still draining accounts and causing havoc. But in practice, this change will probably notably have an impact on cases where there are obvious signs of an impending scam that only the victim can’t see. The future of fraud prevention belongs to banks that can predict which accounts are likely to facilitate fraud and disrupt that path long before police need to intervene.

Acoru provides that predictive visibility: Request a demo here to see how.

What are Bank Impersonation Scams? A bank impersonation scam is where fraudsters pose as a legitimate bank to con the bank’s customers into taking...

What are CEO Scams? CEO scams are a form of social engineering where fraudsters impersonate senior executives to manipulate targets into redirecting...

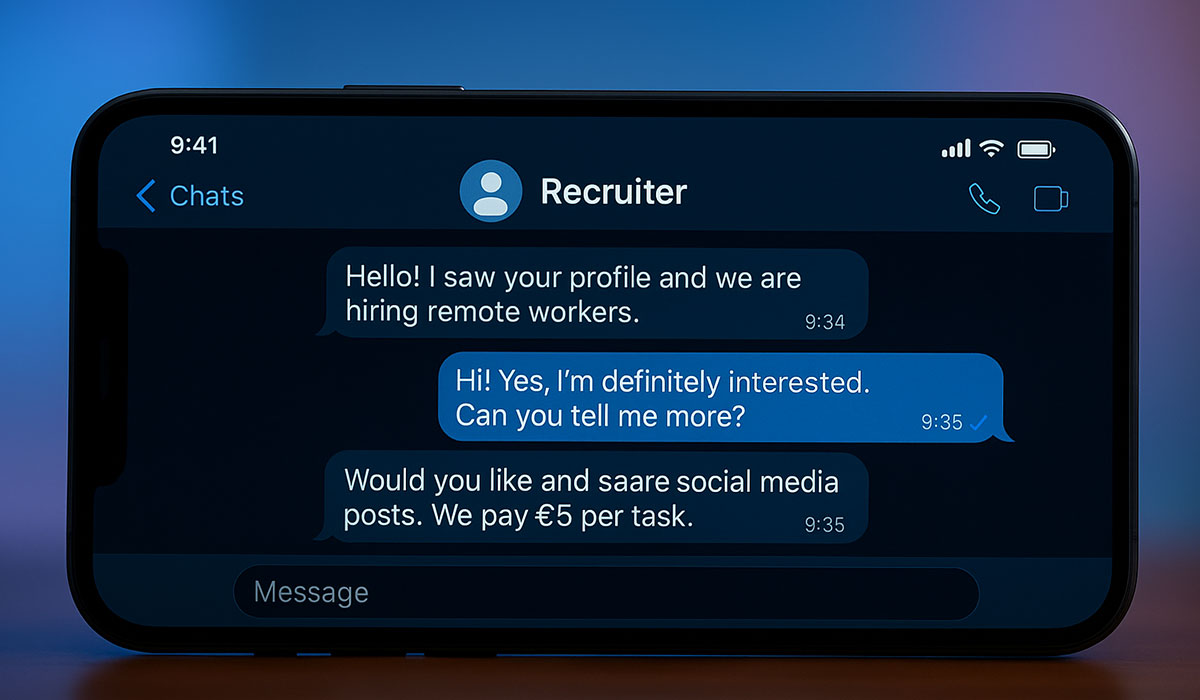

Fake Job Scams are a specific type of authorized fraud (scam). Authorized fraud happens when the person initiating the transaction is the legitimate...